Investment fees are a hot topic these days. Up until recently the investment industry has done a poor job of disclosing their fees, and have assumed that their clients will read the materials they received on the funds they are sold. This lack of transparency allowed some firms to charge outrageously high fees for their services with their clients often being unaware of what they are paying. But fortunately that is now changing with the full roll out of the CRM2 (Client Relationship Model 2) provisions in National Instrument 31-103.

CRM2 is a collection of regulatory changes that came into force on July 15, 2016 with the goal of increasing transparency in the Canadian financial industry. CRM2 requires investment dealers and advisors to provide clients with a new annual report that cost and compensation report that details the amount of operating and transaction fees paid by a client, and the compensation paid to the investment firm in respect of the client’s account.

Let’s take a look at what some of these fees are.

Fund Based Fees

Management Expense Ratio (MER): This is the fee/expense that comes out of a mutual fund every year, you don’t pay it directly. MER is a combination of several different expenses: the management fee that the mutual fund company charges for managing the fund and the expenses of managing the fund (auditors & accountants fees, legal fees, custody fees, etc.) For example, if you had $50,000 invested in a mutual fund for a year, at an MER of 2.5%, you would have paid $1,250 to the mutual fund company to own that fund.

Trailing commission: this is a fee that your investment advisor’s firm receives from the mutual fund company for selling the fund to you. These are paid out of the management fee and MER of the mutual fund. Also called trailer fees, these typically range between 0.25% and 1.00% (but can be higher). Continuing on from our previous example, if your $50,000 mutual fund investment paid your advisor’s firm a 1% trailer fee, you would have indirectly paid them $500 for the year. Keep in mind that only the trailer fee of an MER will show up on the fee report, the rest will not.

Front-end commission: this is a commission that the mutual fund company pays your advisor at the time he sells you the mutual fund. You pay this fee once, and it comes out of your initial investment. These fees typically range between 0% and 6%. For example, if you invested $50,000 in a mutual fund with a 2% front-end commission, you don’t end up actually investing $50,000. Your advisor gives your $50,000 to the mutual fund company, they invest $49,000 in the fund, and give $1,000 to your advisor’s firm as a commission.

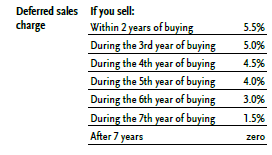

Deferred sales charge (DSC): the dreaded DSC is a fee you may have to pay to sell a mutual fund. Not all funds have them, but they are still pretty common in Canada. Instead of taking your advisor’s commission out of your initial investment like a front-end commission, the mutual fund company pays it out of their pocket (or borrows it). If you sell the fund before a specified time the mutual fund company recovers that cost from you through the DSC. Figuring out how much you will pay as a DSC depends on how long you’ve held the fund.

A typical DSC fee schedule looks like this:

We didn’t make those numbers up, we copied them from an actual fund facts document of a large mutual fund company. If you had $50,000 invested in one of their mutual funds and wanted to sell during the 5th year since you purchased, your DSC would be $2,000! We’ve seen worse too! These are typically based on your original cost, not the fund’s current value, and you can usually sell up to 10% each year DSC-free, but it is still a hefty fee to pay if you need to sell early or you were not aware of the fees!

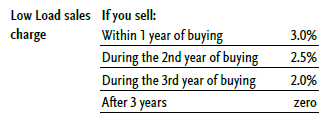

Low Load sales charge: kind of a combination of front end and deferred sales charges. The mutual fund company pays your advisor’s firm a commission up front, but it doesn’t come out of your investment. Instead, if you sell early, the mutual fund company charges you a fee like in the DSC example above.

We didn’t make those numbers up, we copied them from an actual fund facts document of a large mutual fund company. If you had $50,000 invested in one of their mutual funds under this fee option and wanted to sell during the 2nd year since you purchased, your fee would be $1,250.

Switch fees: some mutual fund companies will charge a fee to switch between their different funds or products, the same way you would pay a commission to sell a stock and buy another one.

Short-term trading fee: most mutual funds (except those that are sold subject to a DSC) charge you a fee that ranges from 1-2% if you sell within 30-90 days of buying the fund.

Account Operating and Transaction Fees

Account fees are fairly rare in the mutual fund world, and a much more common at brokerage firms where they have a fee for pretty much everything (I wonder where they got the idea for that, since most of the biggest ones are now owned by the banks!)

Inactivity fee or small account fee: these are typically charged on small accounts that don’t trade very much. It is typically waived if you make a certain number of trades during the year, which means you’ve just paid them trading commissions instead.

RRSP/TFSA administration fee: most financial institutions charge a fee for holding your RRSP and/or TFSA, especially if they are under a certain size. In some cases if you make a minimum number of trades, or your account is above a certain size, the fee will be waived.

Deregistration fee (full and partial): this is what the banks and brokers charge you when you want to make a withdrawal from your RRSP. The fee to make a partial withdrawal is often around $75, and the fee for a full withdrawal can be as much as $150.

Transfer out fees (full and partial): if you want to move your account to another bank or broker, the company you are transferring away from will charge you a fee which can be as much as $200 for a full transfer out.

Unscheduled RRIF withdrawal: if you want to make a withdrawal from a RRIF outside the usual withdrawal schedule, financial institutions charge a fee. Fees to process an unscheduled RRIF withdrawal may be as high as $50. Some banks allow 1 or 2 free before the fee applies.

Wire transfer fee: if you need to take money out of your account and you can’t wait 1 or 2 days for a regular electronic funds transfer, you can have the money wired to your bank account for a fee of around $30, but can be over $100 for large transfers. Many will also charge you a fee to receive a wire transfer and post it to your account.

Trading fees: Fees to trade stocks, ETFs, and other securities (such as options) vary widely. Some brokers now offer free purchases of ETFs and fee sales of a select list of ETFs. But generally you pay $5-10 per trade if placed through an online broker. Fees to trade by phone or through a full service broker are higher.

Management Fee: most common at portfolio managers (PM) and wealth management firms, this is a fee charged based on the size of your account. If you had invested $100,000 with a PM that charges a 1.5% annual fee for an account of that size, you would pay $1,500 for the year.

The above is only a partial list of potential fees that investment advisors and their back offices may charge you.

While no one should work for free (unless they want to!), remember that even if you really like your advisor, at the end of the day this is money coming out of your pocket! You can’t control the returns of the investment markets, but you can control what you are paying.

If your advisor designed a comprehensive financial plan for you and you meet once a year to review that plan and update it, then paying that 5% commission and the ongoing trailer fee may be worth it. If you never hear from the advisor that sold you mutual funds or other products, what did you really get for those fees?

For someone that has been saving all their life for retirement and now has a large account, those fees can really add up to serious $$$. Say your accounts were worth $800,000 and you are in mutual funds that collectively have an MER of 2.3% and pay a 1% trailer fee, your fees would look like this:

$800,000 x 2.3% = $18,400 paid to the mutual fund companies: $10,400 of which they keep, and $8,000 goes to your advisor’s firm.

Are you getting $8,000 in value from your advisor every year? Probably not. Are you getting $10,400 in value from the mutual fund company every year? Probably not. You would be better off choosing a fee-only financial planner to make sure that your financial plan is right for you, and then use an online investment advisor to actually manage the money for you. A good financial planner might charge $3,000 to do the initial plan and $1000 a year for updates and reviews. The online investment advisor might charge 0.35% ($2,800/year) and the products they use might have an MER of 0.20% ($1,600/year). Switching would save you $10,400 in the first year and $13,400 every year after that!

While mutual fund fees of 2% per year might not sound like much, it’s way above the return on a typical “high interest savings account.” When you compound that 2% over 10 years, 20 years, or over a lifetime, when it is time to start making withdrawals in retirement you can have tens, if not hundreds, of thousands less than you would have had if you invested in a low cost option. You can’t change the past, but the sooner you can switch to a lower cost option, the sooner those fee savings start compounding for you in a positive way!